Preserving Minerva Teichert’s Paintings

Peeling Back the Paint: Preserving the Legacy of Minerva Teichert

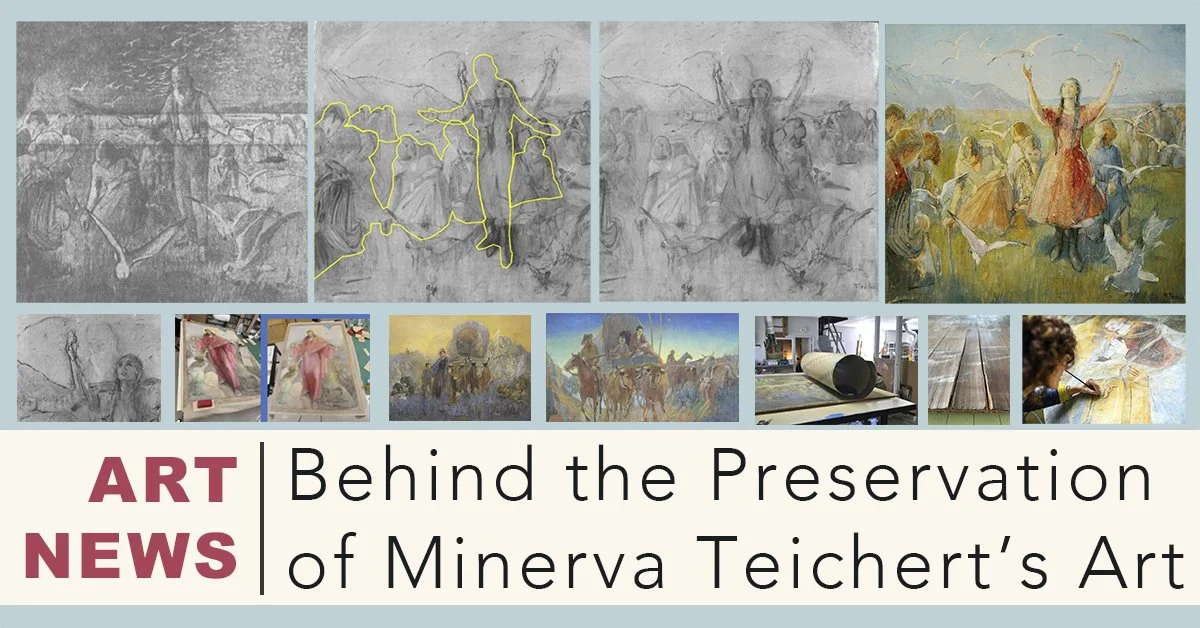

When art curator Laura Paulsen Howe first looked at a 1931 newspaper photo of a lost Minerva Teichert painting, she saw a mystery. The image showed pioneers in a field, giving thanks as seagulls devoured the crickets that had nearly destroyed their crops. At the center stood a bearded man, arms outstretched in gratitude.

The painting was clearly Teichert’s, yet no record of its location survived. Letters from her agent hinted she may have tried to sell it, but historians had no answers.

The riddle lingered for ninety years—until 2021, when conservators cleaning Teichert’s Saved by Seagulls used infrared photography. Beneath its painted layers they found the missing composition, hidden in plain sight. “She must have painted over it sometime before the piece sold in 1937,” Howe said. “We don’t know why, but discovering it was exhilarating.”

That revelation became one of many stories shared by Howe and conservationist Shiree Roberts during a recent Church History Museum forum, Peeling Back the Paint. Their work highlights both the challenges and rewards of preserving Teichert’s art for the future.

A Painter on the Prairie

Teichert (1888–1976) was a rancher’s wife and mother in Cokeville, Wyoming, yet she managed to create hundreds of canvases. Her subjects spanned scripture, pioneer life, and the American West. A friend and advocate, Alice Merrill Horne, championed her career, helping place works in Latter-day Saint meetinghouses, temples, and public spaces across Utah.

But such exposure came at a cost. Madonna of 1847 hung within reach of students at South Cache High School. Not Alone spent years in a church gymnasium. By the time conservators received these works, they bore scars of decades of neglect—tenting paint, frame damage, even graffiti-like pencil marks.

“Sometimes it was hard to tell if a graphite line was Teichert’s or a student’s doodle,” Roberts recalled. Teichert often sketched on canvas and occasionally drew over finished paint. Distinguishing between the artist’s hand and a child’s graffiti required painstaking analysis.

Restoring What Time Took Away

Conservation, Roberts explained, is part science, part art. Madonna of 1847 required heat and adhesive to flatten curling paint, careful fills to repair losses, and a new backing to stabilize the canvas. Not Alone was so large that an eight-person team had to remove its frame just to maneuver it through a doorway before treatment.

Madonna of 1847 - by Minerva Teichert

Every decision demanded restraint. “We’ve got to respect the artist when we do these things,” Roberts said. “Our job is to preserve—not reinvent—what Minerva created.”

Howe noted the inherent tension: curators want paintings visible to the public; conservators want them shielded from light and touch. “Sometimes it feels like a tug-of-war,” she admitted. “But finding that balance is deeply satisfying.”

Science Meets Spirit

The hidden seagull painting revealed under Saved by Seagulls illustrates how modern technology can transform art history. Infrared photography exposed ghostly figures long thought lost, offering a rare glimpse into Teichert’s evolving vision.

At the same time, curators like Howe study her materials and preferences—pigments, varnishes, even her feelings about layering—to guide decisions. “When we conserve a piece, we’re doing our best to do it as Minerva would want it done,” Howe explained.

Roberts added that conservators come from wide-ranging fields—art, history, archaeology, and especially chemistry. Their goal is to extend the life of each canvas by at least fifty years. “We pull skills from all those disciplines to safeguard cultural heritage,” she said.

Preserving for Generations

The Church History Museum’s 2023 exhibition, With This Covenant in My Heart: The Art and Faith of Minerva Teichert, featured 45 original works and gave audiences a chance to see the results of this labor up close. Behind the scenes, hundreds of hours had gone into cleaning, stabilizing, and sometimes rescuing paintings once thought beyond saving.

For Howe, the work is about more than art. “These paintings carry Minerva’s faith and vision,” she said. “Thanks to the dedication of conservators, they’ll continue inspiring generations to come.”